How to make money with a renewable plant

For large projects with decades of life, certainty of revenue is key 🤑

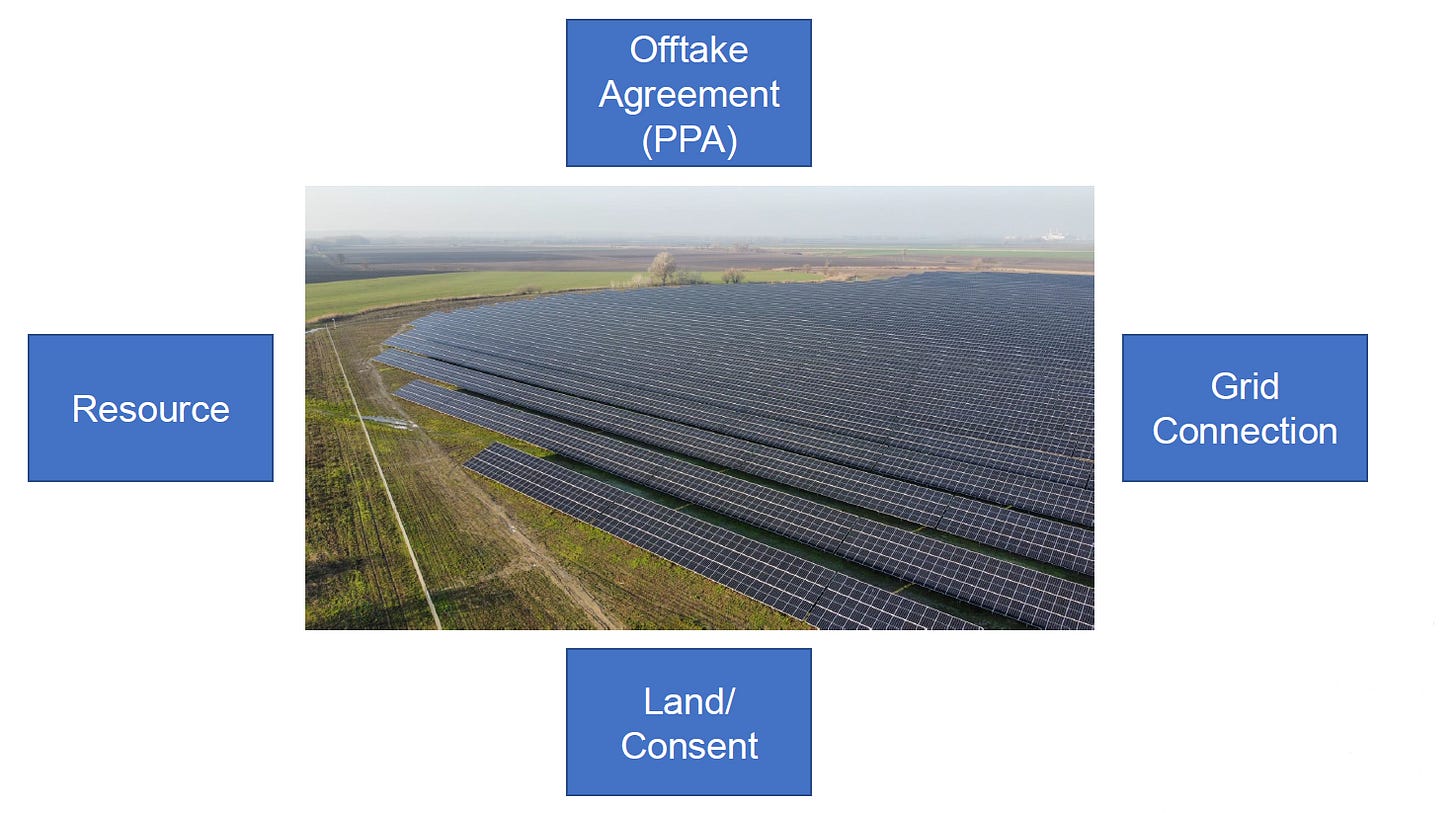

There are “four pillars” to developing a successful renewable project:

Find a good site with sufficient resource.

Acquire land sufficient to develop the resource and obtain resource consent (in NZ, or planning consent elsewhere).

Develop (in conjunction with the network service provider) a grid connection for the project.

Secure an offtake or power purchase agreement (PPA).

All of these aspects are important and each of them can derail a project if not executed well. However, in this post, I want to focus in on item four, securing a PPA, and why this is important. I’ll leave the other items for another time.

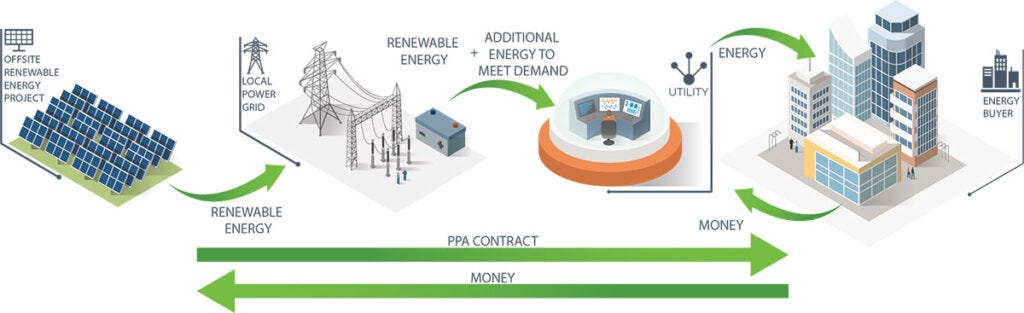

As a renewable project owner, a PPA is a way of ensuring the project gets paid for its energy output at a fixed price. Essentially, it is an agreement with a major load, an energy retailer, or a consortium of smaller loads to agree to buy the energy produced from the project. There are various forms of these agreements, sometimes with multiple price/energy tranches, and sometimes they are complicated with intermediate partners. However, they generally take the form of a multi-year agreement where the purchaser agrees with the seller on a fixed price for the renewable energy.

If you have certainty of revenue from a PPA, it is relatively straightforward to determine if a renewable project is viable. This is one reason why they are popular. Another way of looking at it is, given the known development costs, what is the “strike price” or minimum PPA price to ensure the project is profitable?

You may be thinking that many power networks in the world have markets for electricity and energy is traded in real time, so why not just sell all the project’s output on the open market and the take the best possible price? After all, isn’t renewable energy highly sought after and wouldn’t the project get a great price for its energy? I’ll come back to why this is risky, but first let’s have a look at what it might cost to build a solar project in NZ in 2023, so that we can put some real numbers within this discussion.

To help with this analysis, I made a financial model for a solar farm in NZ. It’s worth noting that this is a simple model and the input values within the model are based on publicly available data, mainly from North America. According to this model, a PPA price of approximately $80/MWh would be enough for a 100 MW solar project in NZ to breakeven.

The result is sensitive to several things including the capital costs of the equipment, quality of resource, whether tracking is used, the cost of land, and the assumed cost of capital (CoC). For example, if the CoC was 3%, rather than the assumed 5%, then the required PPA price becomes $65. Conversely, if the CoC is 7%, then the required PPA price rises to $92.

The cost of capital is an interesting variable to explore, given a project’s sensitivity to it. Generally large scale renewable projects are project financed. This can include a mixture of equity and debt, which combined make up the CoC. IRENA has produced a fantastic report which has surveyed developers to determine what the cost of capital is in each region. Interestingly, it varies widely and there is no data on NZ. Australia is probably the closest relevant reference. Over there, the CoC average for utility solar is reported as 4.6%. Noting here that this report is relatively recent and was published in May 23, but perhaps doesn’t capture the full impact of recent inflation. Nevertheless, 5% for CoC as a starting assumption seems reasonable.

The resource quality is another thing which affects project viability. The shown yield of this project is for a site using single axis trackers (SAT) at the latitude of Huntly. Dropping the yield by 10% has an inversely proportional effect on the required PPA price i.e reducing the yield by 10% means the required PPA goes up by 10%. For this reason, it’s no coincidence that many of the early solar projects in NZ are picking sunny locations in the upper North Island and employing single axis tracking.

Lets come back to the discussion about selling the energy on the open market. Here is where things get interesting and why a PPA for a significant portion of a project’s output is crucial. The average NZ spot price for electricity in the last 12 months varied on a monthly basis between $50 - $160 / MWh. So, you might argue, that all things being equal it is more likely than not that the price would be above our “strike value” of $80 / MWh. In fact much of the time it could be significantly higher than that. “Going merchant” as they say in the industry looks quite attractive. However, the devil is in the detail.

When you offer low cost energy into an electricity market predominantly at a certain time of day that is not highly correlated with load (as is the case for solar in most locations in NZ), you also depress the price at that market node. How much? We can actually answer this question with some confidence thanks to the free market simulation tools provided by NZ’s Electricity Authority.

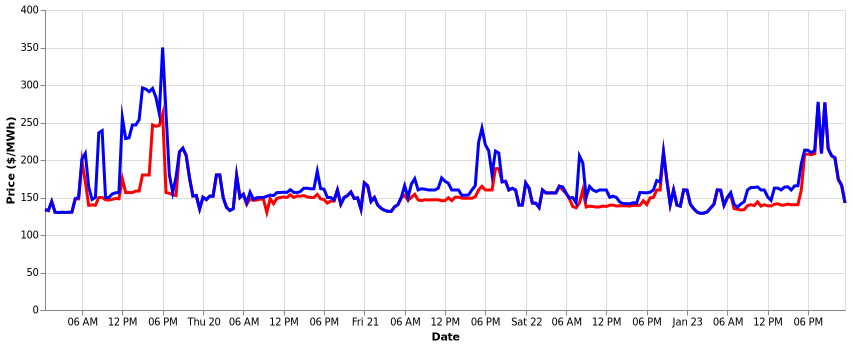

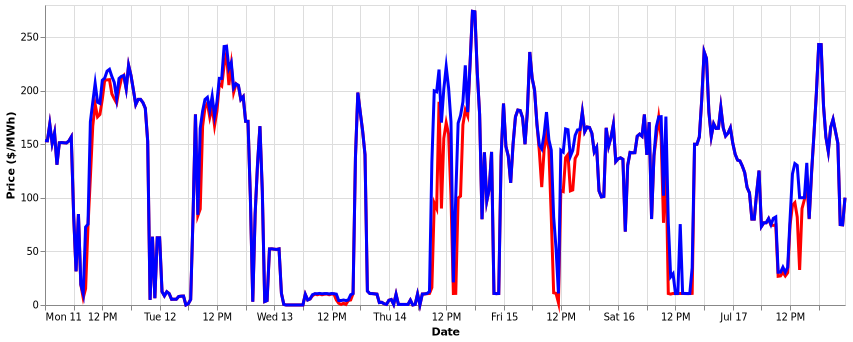

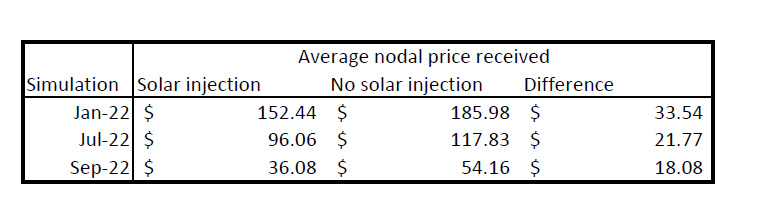

I ran a few hypothetical simulations using vSPD-online which is the Electricity Authority’s tool used to replicate the NZ electricity market. I picked three random weeks in 2022, one in summer, one in winter, and one in spring to observe the effect of additonal solar at a node on the electricity price.

Note that the hypothetical 100 MW solar plant injecting into Huntly has been offered in at $0.01/MWh, which is normal for “must run” renewables to ensure they get fully dispatched and don’t have to curtail output which would otherwise be lost. They don’t end up getting paid $0.01 due to the way the market system works - a good discussion of this is here if you are interested.

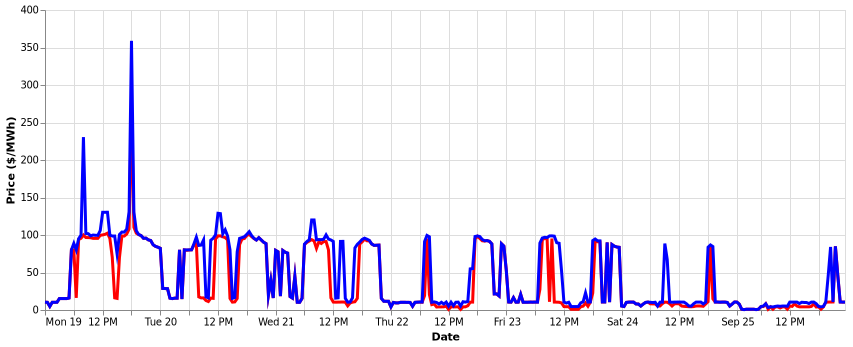

Below are three graphs showing the actual price in blue and the hypothetical price in red if the 100 MW solar plant was available.

The trend in the above charts is quite clear - the red line is consistently below the blue line because injecting “low cost” energy into a node reduces the nodal price at that node. The table below shows the average price ($ / MWh) received by the solar plant in the various weeks, compared with the price the solar would have received if there was no generation. The 100 MW plant moves the spot price by somewhere between $18-$33 / MWh. Imagine, therefore what the impact will be if hundreds of MW of solar connects in nearby locations; the spot price in that area will crash, and your assumption about what you thought the project might earn will be drastically wrong and possibly make the project uneconomic.

Of course, there are some caveats. In reality, when other market participants understand that there are additional renewables, they might alter their offer behaviour and the price reduction might not be as severe as shown. However, the point is, that the price will almost certainly be lower than if the renewable plant was not there.

As you can see from the preceding analysis, selling energy on the open market carries a large risk that you won’t get a price that ensures your project is viable. This is why nearly all renewable projects that reach financial close have a heavy portion of their energy output contracted within a PPA. In fact, many debt providers (aka banks) won’t even fund a project until the PPA is locked in.

NZ is currently facing unprecedented interest in renewables, both from traditional generation developers such as Meridian, Mercury, and Manawa, but there has also been an explosion in interest from new entrants such as Island Green Power, Helios, and Harmony Energy. Transpower’s connection queue is currently over 10,000 MW from 70 projects. We know from overseas experience that many of these projects will not reach financial close and get built.

To speculate somewhat, in my opinion, it’s seems that a good fraction of those projects that don’t get built will fail due to an inability to secure a PPA. An even worse outcome for a developer would be “going merchant”, causing the spot price to crash, and the project becomes uneconomic, requiring the developer to make a “fire sale” or being forced to negotiate a PPA under duress.

A PPA gives your project certainty of revenue. Yes, you may not make the short term returns that might appear attractive from a simplistic analysis of market prices. However, energy projects are a long game, and in the long run, stable returns are more valuable than short term high risk. The PPA forms the “fourth pillar” of your renewable project, without it, your project is almost certainly dead.